John Carpenter : The Master of B movies

|

| John Carpenter Movies Ranked |

John Carpenter: The Master of B Movies

Some directors chase Oscars, and then there's John Carpenter — the man who chased fog, aliens, shape-shifting monsters, and synthesizer soundtracks with the enthusiasm of a teenage rebel armed with a Super 8 camera. Carpenter never made films to win statues; he made them stick to your ribs like greasy diner food — cheap, addictive, and unforgettable.

A true pioneer of genre cinema, Carpenter's influence looms large over modern horror, sci-fi, and action films. He worked mostly outside the studio system, and when he did step into it, he often brought a sledgehammer to the rules. Let’s dive deep into the five defining phases of his journey — the rise, reign, rebellion, retreat, and rebirth of a B-movie master who never stopped believing in cinema's power to entertain, unsettle, and provoke.

Phase 1: The Film School Rebel (1969–1978)

Carpenter's story began at the University of Southern California’s School of Cinematic Arts, one of the country's premier film schools. It was here he co-wrote and scored The Resurrection of Broncho Billy (1970), which won the Academy Award for Best Live Action Short Film. But even with Oscar gold in his early years, Carpenter set his sights elsewhere: genre filmmaking.

His first major project, Dark Star (1974), was essentially a student film turned cult phenomenon. Co-written with Dan O'Bannon (who would go on to write Alien), Dark Star was absurd, philosophical, and delightfully weird. It was a cosmic joke, wrapped in existential dread, all produced for less than $60,000. The film introduced Carpenter's minimalist aesthetic, sardonic tone, and his now-signature musical touch.

Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), a tense urban siege thriller, marked his first full professional feature. Inspired by Howard Hawks' Rio Bravo and George Romero's Night of the Living Dead, the film was gritty, stark, and brilliantly economical. It introduced another Carpenter hallmark: synthesizer-driven scores that could generate dread with just a few notes.

Carpenter was starting to find his voice — one that echoed with pulpy paranoia, tight compositions, and an unwavering devotion to suspense.

Phase 2: The Crown Prince of Horror (1978–1984)

|

| Halloween |

Success allowed him more freedom. The Fog (1980) returned to the campfire ghost story with a seaside town haunted by leprous specters. It was eerie, poetic, and surprisingly emotional despite its B-movie trappings. Then came his collaboration with Kurt Russell — a match made in cinematic heaven. Escape from New York (1981) featured Russell as Snake Plissken, the eye-patched antihero navigating a dystopian New York City-turned-prison. It was pulpy and stylish, with a touch of spaghetti western bravado. Carpenter hit a high watermark with The Thing (1982), his nihilistic sci-fi masterpiece based on John W. Campbell Jr.'s novella Who Goes There? Although it was lambasted at release (critics preferred Spielberg's sunnier alien tale, E.T.), The Thing is now revered for its groundbreaking practical effects, its claustrophobic tension, and its chilling ambiguity. The film's failure at the box office nearly broke Carpenter's career, but it made him a legend.

Christine (1983) and Starman (1984) showed his range. The former was a supernatural car thriller adapted from Stephen King, while the latter was a gentle sci-fi romance that earned Jeff Bridges an Oscar nomination. Carpenter could swing between tenderness and terror with great ease.

Phase 3: The Underrated Innovator (1985–1994)

|

| Big Trouble in Little China |

They Live (1988) was pure Carpenter rebellion — a sci-fi satire about consumerism, conformity, and Reaganomics. Starring wrestler Roddy Piper and featuring one of the longest fight scenes in cinema history (over a pair of sunglasses), it was part B-movie romp, part socio-political gut punch. "I have come here to chew bubblegum and kick ass... and I'm all out of bubblegum," became a rallying cry for the counterculture. He closed this phase with In the Mouth of Madness (1994), a surreal dive into Lovecraftian horror. It blurred the lines between fiction and madness, with Sam Neill delivering a manic performance as a man who realizes the world is turning into a horror novel. The film is now considered the final installment of Carpenter’s unofficial "Apocalypse Trilogy" (alongside The Thing and Prince of Darkness).

Phase 4: The Studio Struggles and Slow Fade (1995–2001)

|

| Vampires |

As the '90s progressed, Carpenter's work began to struggle against the tides of changing studio expectations and shifting audience tastes.

Village of the Damned (1995), a remake of the British sci-fi classic, lacked the bite of his earlier works. Escape from L.A. (1996) was a satire of his own dystopian past, with a bigger budget but an intentionally absurd tone that audiences didn’t appreciate at the time. The film featured surfing, plastic-surgery villains, and post-apocalyptic basketball — it was either ahead of its time or just gleefully off the rails.

Vampires (1998) was Carpenter's stab at the vampire genre, and while it featured brutal action and Western grit, it divided critics and fans. Ghosts of Mars (2001) was meant to be a return to form, but poor box office returns and critical reception led Carpenter to step back from directing.

This period was marked by frustration, as his unique voice was increasingly drowned out by Hollywood's obsession with polish and formula. But even these "lesser" works carry his unmistakable fingerprints — synths, shadows, and an uncompromising vision.

Phase 5: The Legend in Rewind (2005–Present)

|

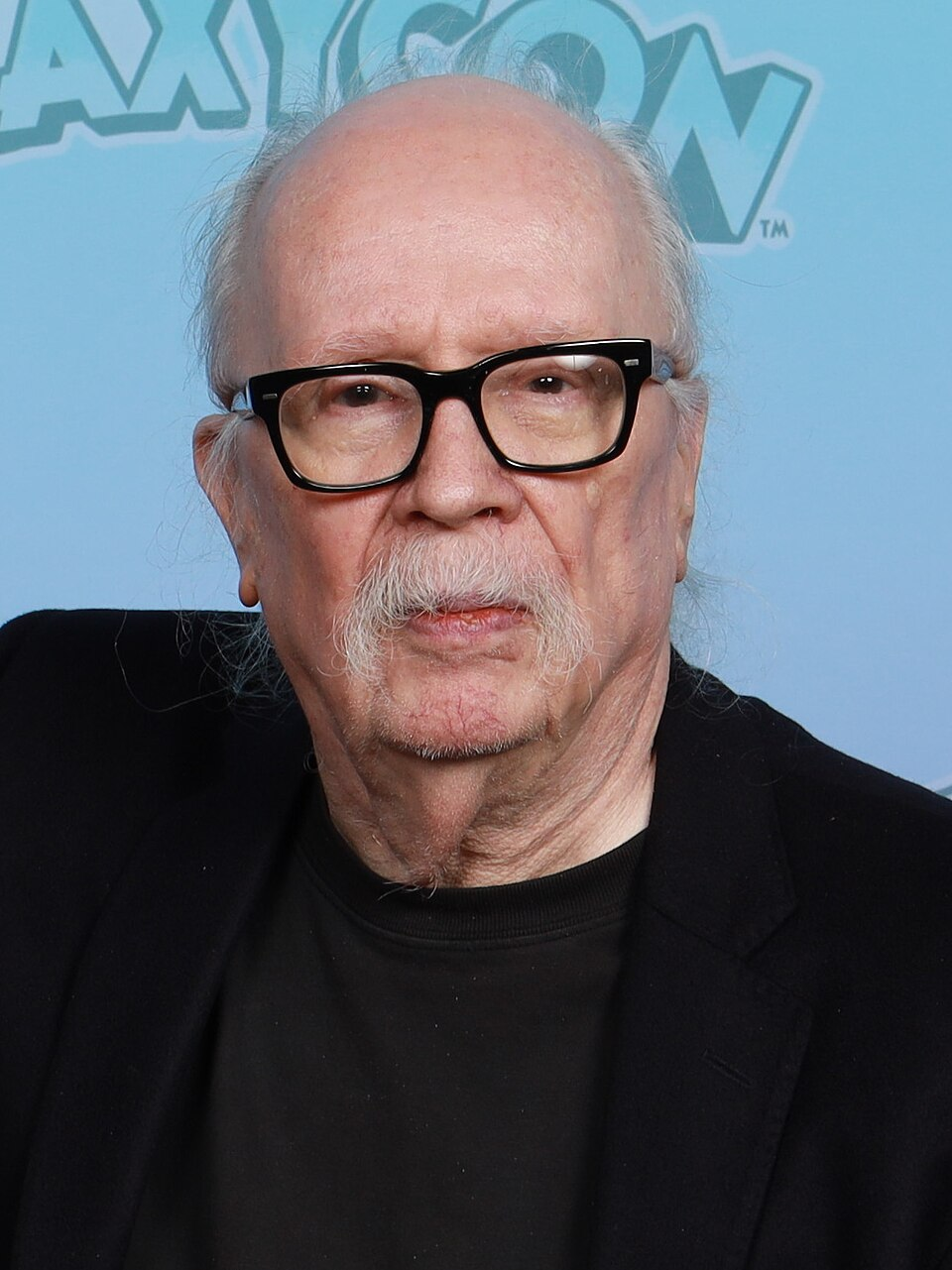

| John Carpenter (now) |

Yet Carpenter's true renaissance came not through film, but through music. His Lost Themes albums (released in 2015, 2016, and 2021) featured original synth compositions in his signature style. These moody soundscapes evoked cinematic images even without visuals, and Carpenter began touring internationally as a musician — a surreal but fitting evolution for a man whose soundtracks were always half the magic.

His influence now echoes throughout pop culture. Filmmakers like Robert Rodriguez, Quentin Tarantino, James Wan, and David Robert Mitchell (It Follows) have cited him as a major inspiration. Stranger Things wears his influence like a badge of honor. Even gaming and comic books have embraced his legacy.

Today, Carpenter enjoys the respect he always deserved. He never compromised. He created what he wanted to see, regardless of trends or expectations. He is living proof that B-movies, when made with heart, talent, and vision, can outlast the so-called "A-list" productions.

Final Cut

John Carpenter is more than just a director — he's a genre unto himself. He built an empire on the fringe, crafting tales of paranoia, rebellion, and survival that feel as relevant now as they did decades ago. His characters don’t save the world; they endure it. His films don’t ask for permission; they kick the door down and start the fog machine.

In a world of glossy CGI and franchise fatigue, Carpenter's rough-hewn, analog style feels like rebellion. And maybe that's why we keep coming back to him — because he reminds us that the soul of cinema isn’t in its budget, but in its bite.

Cue the synth. Fade to black.

Comments

Post a Comment